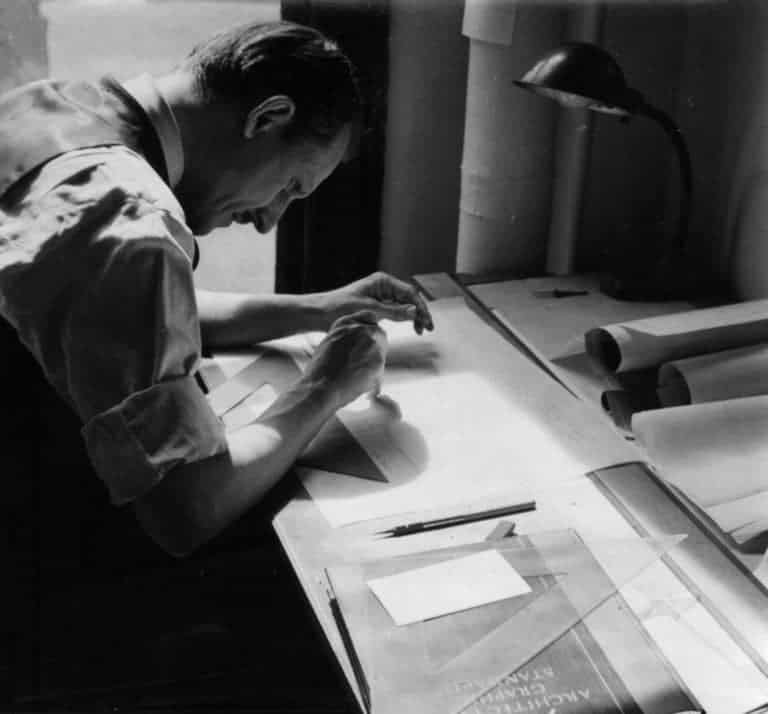

My father, W. Lindsay Suter, was one of the architects of the Heart Mountain War Relocation Center near Cody, Wyoming. Too young to serve in World War I and too old for World War II, my father specialized in designing houses and small commercial properties along with his architectural partner, René Travelletti. However, once the United States entered World War II in late 1941, domestic construction ceased almost completely. Both men had families and needed work, so they looked around to see how they might contribute to the war effort. The Harza Engineering Company of Chicago was advertising for architects and engineers to design and supervise the construction of an internment center for Japanese Americans in Wyoming. They decided to sign up.

My father must have believed he would be able to make the internment center as habitable as possible, a notion of which he was surely disabused in short order. Dad never shared anything about this project with me, and I never asked him about it. I learned the details from my mother some thirty years later, when I happened to ask her what we were doing in Wyoming back then.

Fourteen thousand people of Japanese ancestry were incarcerated at Heart Mountain during the period the camp was open from 1942–45. Once I understood the meaning of that summer long ago, I began to contemplate a pilgrimage to the Heart Mountain site. But I learned that all that was left of the camp was a ramshackle old building and a deteriorating memorial.

I let go of the idea for nearly four decades, until 2005, when one day, on a whim, I searched for “Heart Mountain” on the Internet. To my amazement, I found an active website describing a comprehensive interpretive center, a bookstore, staff members, and a foundation devoted to the history of the camp. Furthermore, the center was holding yearly events called Pilgrimages, to which former incarcerees, their families, friends, and any interested parties were welcome. Fifteen hundred people had attended the first Pilgrimage in 2011. Immediately I knew that I wanted to go to the next one, scheduled for summer 2016. I ordered some books and a video from the bookstore, registered to go to the event, and reserved a room at a motel in Cody.

On July 27, I drove the 105 miles from the airport at Billings, Montana, to Cody, Wyoming, returning after an absence of seventy-four years. Driving in darkness for the last thirty miles or so, I could just make out the dark purple outlines of mountains against a moonless sky. I was tired and anxious, not only about staying on course with no lights to guide me along the desolate road, but also about how I would be received at Heart Mountain by people I had never met and who might have reason to dislike me.

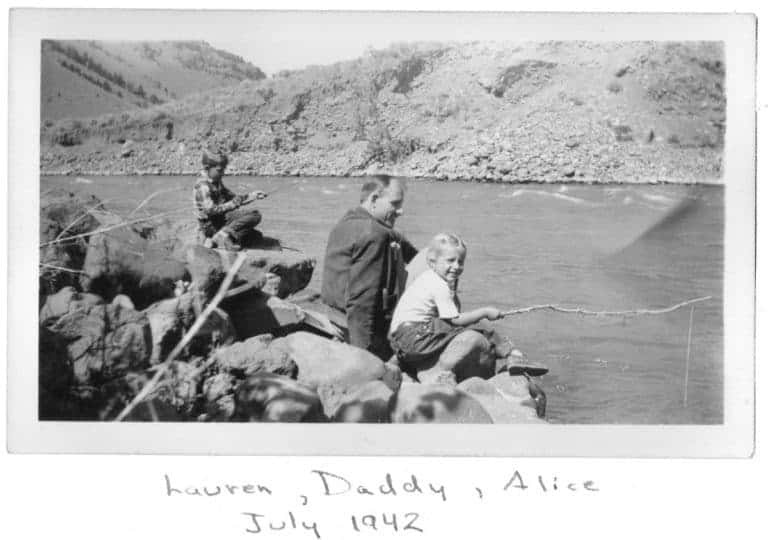

The author with her father in Wyoming Photo courtesy of the author

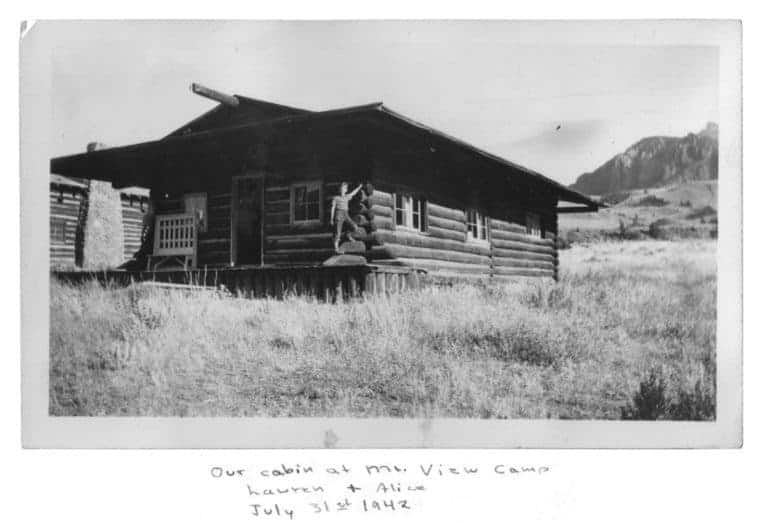

In May 1942, my father had taken the train from our suburban home in Winnetka, Illinois, to Cody, where he began his work. A few weeks later, my mother, my older brother, Lauren, and I met him in Wyoming. After a short stay in a tourist cabin, we settled at Majo, a working ranch on the South Fork of the Shoshone River. We took to ranch life with gusto, living in a log cabin beside a spring where we drew our water every day. We ate our meals with the ranch family and staff, downing huge breakfasts of eggs, bacon, and my favorite new food, flapjacks. Lauren and I rode a gentle old horse and gathered deer and elk antlers in the surrounding hills. We also played a water-engineering game that we called “Dam the Shoshone,” redirecting the little rivulets that ran alongside the shallow river. It was the first time I remember the two of us playing well together, without the constant squabbles typical of our life in Winnetka. It was one of the happiest summers of my life.

My father came out to the ranch on weekends, riding in the mail stage, a pickup truck that delivered mail, groceries, and other necessities to the ranches along the South Fork. Lauren and I were sometimes allowed to ride in the pickup and throw bags of mail into the mailboxes’ large openings as the truck sped along. The Shoshone was full of trout, and Dad often took us fishing. Our equipment consisted of long sticks, strings, hooks, and grasshoppers. When I caught my first fish I screamed so loudly that I’m sure any others were scared away.

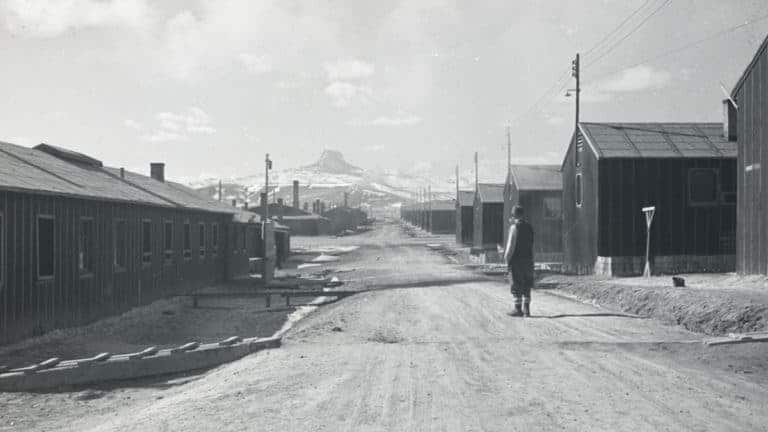

One time, Dad took the family to see what he had been working on during the week. I have no memories of what I saw. But I can imagine myself, a restless five-year-old looking at a city of tar-paper barracks stretching off into the sage, impatient to get back to my games and the Shoshone River. Only a few weeks after our visit, thousands of Japanese American children and their families walked into that same city, into what might have been the worst period of their lives.

I was vividly reminded of that contrast as I drove out to the relocation center. I had read about the Japanese American experience of mass incarceration in ten different camps throughout the West, and about the Heart Mountain experience in particular. It had increased both my understanding and my anxiety. I felt a bit like an interloper. I knew I needed to be candid about my interest and my father’s role, but how would people judge me?

From the road I could see the small, barrack-like building that houses the interpretive center, and the gardens immediately around it. Beyond lay a desolate plain.

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) had chosen to site the camp on a flat stretch of high desert dotted with sagebrush and buffalo grass, and dominated by an unusually shaped mountain to the northwest. Heart Mountain is an 8,123-foot rock mass remaining after the surrounding material has eroded. The mountain appears heart-shaped from Cody, but it looks more like a thick pillar or an anvil when viewed from the camp. Legend has it that Heart Mountain was blown up by a volcano and thrown for several miles before it landed in its present location, upside down. Geologists believe that its placement atop rocks much younger than itself is actually the result of a catastrophic slide triggered by a now-extinct volcano some twenty-five miles to the northwest of the current site. All of this happened some fifty million years ago, but it provides a dramatic prologue to the tumultuous journey of incarcerees to this site during World War II.

On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, requiring all people of Japanese ancestry, both those born in Japan and those born in the US, to leave their homes on the West Coast immediately as a “matter of military necessity.” They were to abandon their homes, farms, and belongings, and take with them only what they could carry.

In March 1942 President Roosevelt appointed Milton Eisenhower, brother of General Dwight Eisenhower, to direct the newly created WRA. On orders from the president, Milton Eisenhower informed several governors that so-called internment centers for Japanese Americans would be built in their states. During the war and for decades after, government officials and the public referred to these camps as “internment” or “relocation” centers, and to their inmates as “residents.” President Roosevelt referred to the facilities as concentration camps, places where people were forcibly incarcerated without due process.

Construction at Heart Mountain began in June 1942, under the supervision of the US Army Corps of Engineers. The work was carried out mainly by private contractors. The government soon informed the Corps and its contractors that more than ten thousand people were on their way and that they had only sixty days to complete the construction. The project was much more extensive and had to be finished much sooner than anyone had anticipated. Ads for workers said anyone who could drive a nail could apply for a carpenter’s job. Inspectors overlooked poor workmanship because of the need for haste.

As a result of the accelerated schedule, architects and draftsmen simplified the design, cut corners, and use prefabricated materials. They used lighter-weight roofing materials for those originally specified and cheap tar paper to clad the exterior, abandoning the plans for insulating the barracks. The buildings were framed with uncured lumber that shrank when it dried, forming large cracks through which sand, dust, and dirt blew in, not to mention the freezing cold winter air. Because of the wood shrinkage, doors and windows often didn’t close. Many of the woodstoves, which were the only source of heat, were improperly positioned, sometimes resulting in fires. The wiring for electric lights was often installed incorrectly, and the water system was designed without expansion joints, so the water lines broke and pipes froze continually during the record-cold months of the first winter.

Construction was completed in sixty-two days, almost on time. In addition to more than 450 barracks, the workers built eight office buildings, a recreation and mess hall, a hospital, a sewage treatment plant, a power station, and some warehouses. Barbed-wire fencing completely surrounded the compound, interspersed with eight forty-foot guard towers.

In August 1942, the first incarcerees walked into this makeshift city—men in their suits, women in their Sunday hats and spectator pumps, little girls in dresses. More than six thousand Heart Mountain incarcerees were from the Los Angeles area. The parched, treeless desert of Wyoming was foreign enough, but the inmates also weren’t prepared for the bitter cold and had no winter clothes. The government eventually supplied them with Navy surplus pea coats, but most of the incarcerees had to buy winter clothes to survive the subzero temperatures.

Families were squeezed into barracks that contained six single-room apartments of 320 square feet each, and one of 480 square feet for six-person families. A bare bulb dangled from a single electrical outlet, and the only furniture consisted of cots and mattresses. Mess halls and latrines were located in separate buildings. For the first several months, food was in short supply and of very poor quality, causing hunger and overcrowding in the camp hospital. People had to go out into the freezing cold to relieve themselves no matter the hour, often triggering the searchlight from the nearest guard tower. There was no privacy. Showers and toilets, although divided by gender, were communal, and there were no partitions.

I knew my father as a perfectionist, and being responsible for that kind of shoddy workmanship must have been painful for him. Although he was usually mild-mannered, I occasionally heard him yelling at contractors over the phone about missed deadlines, electricians or plumbers who hadn’t shown up, or jobs that had been done sloppily. I don’t know how he felt about his role in the imprisonment thousands of families, because we never spoke about it. He lived to the age of ninety, so he must have known about the reparations movement, the hearings, the payments to incarcerees and their children, and the eventual apology by President Reagan to the Japanese American people. Perhaps he felt some guilt, and that is why he never brought it up. I never broached the subject with him, and to this day I consider it an opportunity squandered.

The author’s family’s cabin at Mt. View camp in Wyoming Photo courtesy of the author

With a sense of foreboding, I parked the car and walked into the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center. I was greeted at the door by Shigeru “Shig” Yabu, who introduced himself as a member of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation board of directors. During his family’s incarceration, Shig found and tamed a magpie, who became his constant companion. He and his magpie were the subject of two children’s books, which he pointed out in the center’s bookstore. I picked out two copies for my granddaughters.

When Shig asked what brought me to Heart Mountain, I explained that I’d spent the summer in Cody when I was five because my father was an architect of the camp.

“No kidding!” he said, his eyes lighting up. “That’s wonderful! I’m very pleased to meet you.”

There was a cheerful hubbub in the interpretive center as old friends greeted each other and introduced family members. The staff and board of directors had planned a two-day weekend of workshops, dinners, and speeches. Friday afternoon we were invited to attend a forum in which organizers divided attendees into small groups of about twelve participants each; every group included a facilitator and at least two individuals who had been incarcerated at Heart Mountain.

We were welcomed by Shirley Ann Higuchi, a dynamic attorney from Washington, DC, who also chaired the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation board of directors and facilitated our small group.

She identified herself as a Sansei, a third-generation Japanese American. Her parents had met in the Heart Mountain camp. She asked us to go around the circle to introduce ourselves and say something about our connection to Heart Mountain. My heart skipped a few beats.

Many in the circle had been incarcerated at the camp as children and described the activities they enjoyed, such as weekly dances, sports, and being around other kids their age. One of those people, Lili Tokuda, who had arrived at the camp when she was nineteen, said, “The ones who suffered were the parents, but they never complained.”

Shig Nishida had also been incarcerated at Heart Mountain as a child; his wife, Rae, had been at the Minidoka camp in Idaho. Shig said he usually ate meals with his friends while his mom worked in the mess hall. “It destroyed the family dynamic,” he said, breaking down.

Finally, it was my turn. I felt shy but not intimidated. The friendly reception by Shig Yabu in the bookstore had given me courage. I told them about my father’s role as an architect and construction supervisor and how I had not known about it for decades. I also told them that the summer of 1942 was the happiest of my childhood, that the irony of that fact was not lost on me, and that I felt a deep sadness about the suffering of the Japanese American people. Although no one spoke, I sensed that I was not being judged.

At one point, Shirley also talked about how many in the Nisei generation didn’t want to talk about their incarceration experiences with their children. She described a typical conversation with her mother:

“Hey, Mom, tell me something about how it was in the camp.”

“It was where I met Dad. It was a fun place to be.”

“Oh, come on, Mom, weren’t you angry?”

“No. I was happy.”

“Really? You weren’t angry?”

“I was happy! I was happy!”

“Mom, why are you yelling?”

The reluctance to discuss the camp experience was a common theme among the people I met at Heart Mountain. “If nobody talks to you about it,” Shirley observed, “you don’t know who you are!” I couldn’t help noticing the parallel with my own father’s silence about this epoch in our family’s life.

On Saturday morning I met with Tlaloc Tokuda, Lili Tokuda’s son. He shared none of his mother’s sunny attitude about the camp experience. Although he was born after his mother left the camp, he had very strong feelings about the incarceration. Tlaloc’s parents had named him Greg, but he explained that he felt betrayed by the American government and didn’t want an American name. He changed it to tlaloc, the Toltec word for “cloud.”

Now in his early seventies, Tlaloc told me that as a young man his eyes were opened when he started to read about racism and the treatment of Blacks and American Indians, so he dropped out of high school and began working in Black communities in Los Angeles. “I don’t think of myself as American,” he said, weeping quietly. “In fact, I’m really ashamed of America.”

That afternoon I explored the interpretive center’s award-winning exhibit about life in the Heart Mountain camp. It described how, despite their privations, the incarcerees attempted to normalize their lives: Children played games, did their homework, and graduated from high school. People got married and had babies. Some died. Families hung sheets as privacy curtains and built their own furniture using tools they ordered from the Sears Roebuck catalog. They planted individual and community gardens and cultivated several thousand acres of arid land, producing flowers and vegetables, to the amazement of the locals. The harvest of 1944 yielded 2,500 tons of produce. A camp newspaper, the Heart Mountain Sentinel, helped provide a sense of community. Residents organized a variety of activities, including Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, and several types of sports teams. They practiced traditional cultural activities, holding classes in flower arranging, haiku, and Japanese music, as well as kabuki theater performances.

In the blazing heat of the late afternoon, I walked across a nearby field to visit an original tar-paper barrack that had recently been brought back to the site. Moving through it I was struck by how small it was, though it was meant to house several families. It was more like an outbuilding on someone’s farm, or a shed in someone’s backyard. A typical room, designed for a whole family to live in, was smaller than my living room. Outside the barrack, I stopped to chat with a family who had also come to the Pilgrimage. I had begun to feel more relaxed about introducing myself. More than one person had said, after learning my story, “Wow, that’s really interesting! Hey, come and meet Alice. Her father was an architect here!” Colleen Miyano and her siblings and cousins were no exception. They had come to honor their parents and their uncle, Ted Fujioka, who had graduated from Heart Mountain High School in 1943, where he was student body president. Fujioka was one of the young men who volunteered for the army while his family was still incarcerated. He was a member of the famed 442nd Regimental Combat Team, composed entirely of Japanese Americans, the most decorated unit of its size and length of service in US history. He was also the first soldier from Heart Mountain to die in combat in World War II.

Americans of Japanese descent were among the first to speak out against anti-Muslim propaganda immediately after the 9/11 attacks. They knew that what happened to their parents and grandparents could happen again. Inspired by the civil rights movement of the 1960s, both Nisei and Sansei also played an active role in the Japanese American redress movement of the 1970s and ’80s. In 1988, Congress agreed to pay $20,000 to each of the living survivors, amounting to a total of $1.6 billion. And, of greater importance to the survivors, the US government issued a public apology. Senator Daniel Inouye, the first Japanese American to serve in the US Congress, fought for the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 and redress to the Japanese Americans. In 2013, President Obama awarded Inouye the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously. Slightly younger than Inouye, Norman Mineta also served in Congress for twenty years before he became Secretary of Commerce and then Secretary of Transportation. “Commit yourself to public service,” reads a plaque at Heart Mountain that bears Mineta’s name. “Be accountable and accessible, and what happened here will never happen again.”

On Sunday morning the group dispersed, all of us going our separate ways. Leaving Cody, I drove north along the desolate plain of the Bighorn Basin, where I could see the anvil silhouette of Heart Mountain against a brilliant blue sky. I was grateful for the kindness everyone had shown me and for some new friendships. I wished I could have told my father all about it, and I think he would have been pleased to listen.

4 thoughts on “To Heart Mountain”

Bill and I have been to Heart Mt. in 2011 before the interpretive center opened. Your story is one of many American stories; most haven’t been written down! Thank you for writing yours.

There was one Japanese family (Hayashi) in my small North Dakota town. They owned a restaurant where my parents took us for breakfast after Mass every Sunday before driving back to our farm.

I’ve been curious about the Hayashis and now you’ve renewed my curiosity. I wonder if they came from an internment camp and didn’t go back to live wherever they were from. More stories to unearth!

We should compare notes about Heart Mountain!

Even though I’ve been on the inside of this story, every time I hear another experience of it I get teary. It was so brave of this woman to return to Heart Mountain. Even more brave was the non judgmental reception by the Japanese American people she met there. Isn’t that what we’re missing now? I think acts of kindness (not my original idea) are the most important thing we can do right now. Thanks for sending it!

Janet, friend of Marie’s

Marie–so glad you passed this along. It’s really haunting. And I can’t help but wonder what kinds of stories will be written in 50 years or so about people’s experiences as children in the hands of ICE. It’s as if we simply steadfastly refuse to learn from past mistakes. Which of course makes stories like this all the more important. Thanks again.

Dave