Bonnie McKinlay arrives at my house a little out of breath, greets my dog, and apologizes for being late. She’s wearing a Norwegian wool sweater and a huge backpack full of materials. Although she almost always rides her bike, this time she has driven because she’s taking people with her to testify at a hearing in Longview, Wash. I’m a little surprised to learn that she actually has a car.

Despite her 64 years, she has few gray hairs and a great deal of youthful energy. Although soft spoken, it’s clear that she can be vigorously persuasive.

We settle in at my dining room table with a simple lunch of salad, cornbread and tea. Before we’ve taken more than a few bites, the conversation gets right down to basic essentials and I reach for my notepad.

“We are in crisis,” she declares. “When will people wake up to that?” Bonnie assumes that everyone knows about the consequences of climate change, that those who deny them are either bought and sold or just ill informed by the media, that the secrecy surrounding the Trans-Pacific Partnership and its implications for climate are malevolent, and that the consequences for future generations are catastrophic — unless we do something to change the course right now.

“Our planet’s climate is allergic to carbon. We know that. If your child were allergic to carrots, for example, you wouldn’t keep feeding her carrots, would you? Why are we doing this? What is more important than the civilization that would be lost?”

She’s referring to the loss of multiple species of animals and plants, people’s homes and families through mass migration, cultures, literature, music, lives, all the consequence of unmitigated climate disruption.

Bonnie grew up on Long Island until age 12, when her family moved to Southern California. Her parents always encouraged her and her brother to speak out, to raise their voices whenever they felt that people were being treated unfairly or when moral issues arose. During the civil rights movement Bonnie longed to go to Washington, D.C. and join the marches, but she was too young. Instead, she sold hand-made potholders in the neighborhood and donated the money to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

At 18 she moved to Portland, where her brother had gone to Reed College. Here she earned her teaching credential at Portland State University, got a master’s degree in media studies, and went to work as an elementary school teacher and librarian. She enjoyed working with children, helping them understand subjects experientially, not just from books. She remained drawn to issues of political and social justice.

“I have always been an activist,” she explains. “There is a human tendency to shove things under the rug, and I find myself fighting against that.” During the Vietnam War, as Bonnie protested, her brother refused the draft and somehow managed to carry it off, and her husband, Jim, was a conscientious objector.

Bonnie is a natural organizer. Over a period of several years, she and her friends and family put on meal fundraisers. They would empty their house of furniture, bring in lots of tables and chairs, invite the community, and serve a big meal. They held raffles and games to raise money. Right after the Haitian earthquake they raised $8,000 for Doctors Without Borders. Later, with the organization 350.org, they raised $3,000 for relief efforts in the Philippines after Typhoon Yolanda. She and friends went on to use this method fundraising for several other causes.

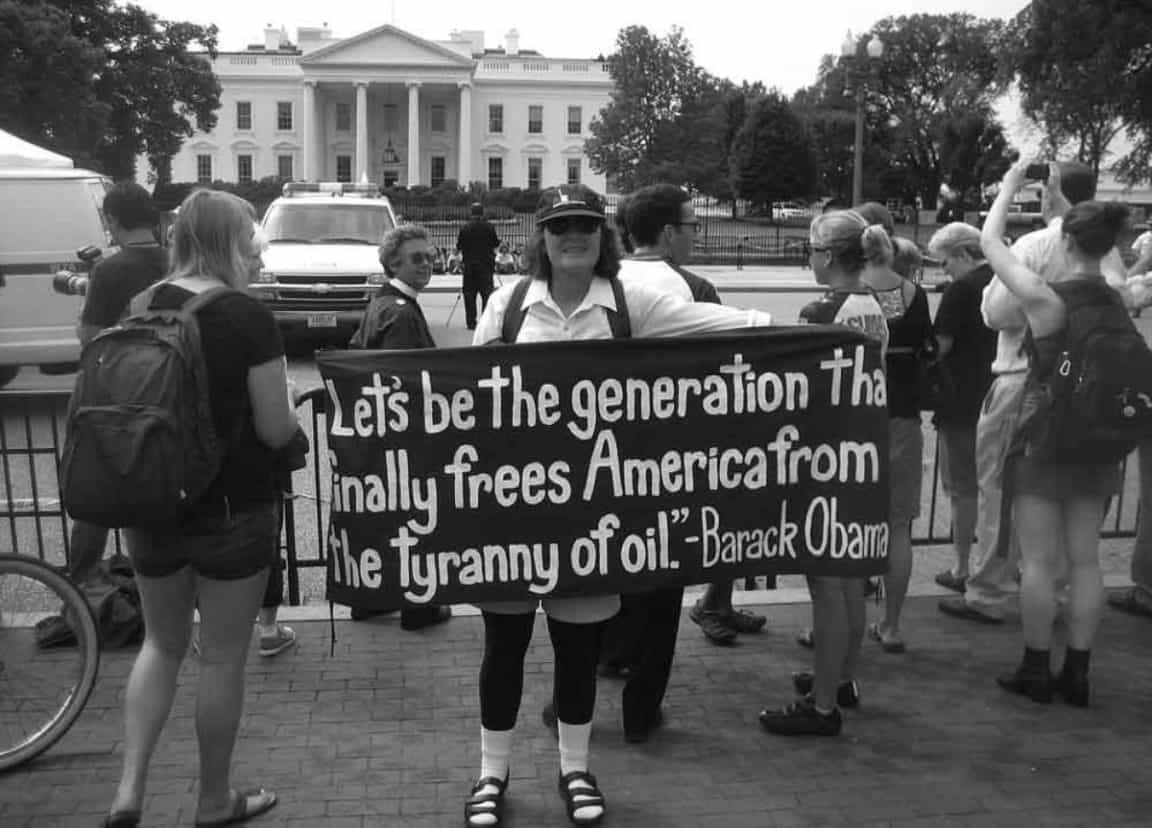

Then in the summer of 2011 there was a call-out from Bill McKibben, the well-known author and co-founder of 350.org, to come to Washington, D.C. It was just after the famous statement by former NASA scientist James Hansen that the Keystone XL pipeline would be “game over” for the planet because of global warming. “Jim and I looked at each other and said, let’s go!”

They took the train because they had sworn off flying, and when they got to Washington they took the civil disobedience training from 350.org. They stood in an area near the White House where people are allowed to stay for only 20 minutes, and they stayed rooted there. The police warned them three times that if they didn’t leave they would be arrested. And so, of course, they were arrested, along with 1,251 other demonstrators over a two-week period. Right in the center of the group stood Bill McKibben, with other movement luminaries, all of whom ended up in jail.

“About 25 of us women arrestees were crammed into a 10’ x 10’ cell with a toilet,” Bonnie reports. “Then we were moved to a slightly bigger cell with fewer women. We spent the weekend there, in that cold room on a dirty cement floor, with the lights left on day and night. One woman was taken to the hospital with a bad migraine. But the rest of us played word games, talked, sang and did yoga. Nobody could sleep. We were finally released on Monday afternoon.” Despite the hardships, Bonnie says it was one of the high points of her life. “The setting was terrible, but it was a wonderful experience,” she says emphatically, “I would never give it up. Not for a second.”

Shortly after the protest in D.C., Bonnie and Jim became involved in the Occupy movement. Now she is deeply involved in several organizations combating climate change, including NoKeystoneXL, Portland Rising Tide and 350.org. She has been a diligent worker for the NoKeystoneXL effort in Portland, convening meetings, organizing outreach, and writing comments to agencies and public officials. She makes posters, signs and informational flyers and gets other people to do the same. She designs actions, organizes rallies and parade entries, and keeps her vast e-mail list up to date, notifying us about upcoming events and sending out links for articles of interest. She does many of these activities for other climate organizations, as well.

When she talks about the Alberta tar sands project, that enormous Canadian strip-mine where miles of boreal forest have been cut down to extract oil, Bonnie’s vocal level moves up a notch: “I ask people: ‘Have you seen it?’ This area is as big as Florida and totally uninhabitable! There is no reclamation. They’re destroying animals, tribal areas, everything. They have taken one of the best carbon sinks anywhere in the world and made it into a wasteland. There are strange cancers among the First Nations people down river. In some places they’re hydro-fracturing underneath the forest.”

“Calling this area a natural resource is ridiculous!” she insists, her voice rising still higher. “That diminishes the value. It’s not just a natural resource; it’s life we’re talking about.”

According to Rising Tide North America, one of the organizations Bonnie works with, there are 28 proposed fossil fuel projects in Oregon, Washington and British Columbia. That means oil and coal trains, pipelines, terminals, and refineries. To the question of why Oregonians should be involved, Bonnie answers: “We on the West Coast are a super highway for fossil fuels — coal, oil, and gas. It’s not that large-scale extraction is done here, but the fossil fuel industry plans to have its carbon-based commodities move through our land and waterways en route to the coast.” According to Rising Tide North America, one of the organizations Bonnie works with, there are 28 proposed fossil fuel projects in Oregon, Washington and British Columbia. That means oil and coal trains, pipelines, terminals, and refineries.

She moves her lunch plate over and unfolds a large map entitled “Coal, Oil, Gas: None Shall Pass.” She spreads it out on the dining room table. It shows a spider web of pipelines and rail routes, some existing and more proposed. They extend from inland extraction projects throughout western Canada and the United States, including the Alberta tar sands, countless fracking fields, and the coal strip mines of Wyoming and Montana. All are headed toward facilities up and down the coast and the Columbia River, where the cargo is to be loaded onto barges and tankers bound for West Coast refineries or export to Asia.

“These projects may be regional, but in terms of our corrupted climate, their impacts are global.” Our lunch lies unfinished, and I have to write fast to keep up with her.

Along with her continued work on regional coal and oil projects, Bonnie is teaming up with state-wide efforts to bring awareness of the LNG (liquefied natural gas) terminals planned for Warrenton and Coos Bay. In the process of liquefying the gas, methane frequently escapes, creating a fire hazard and contributing to climate heating significantly more than equivalent amounts of other fossil fuels.

“The problem is that it’s so hard to reverse something once it’s built and when people have jobs.” But there are already proportionately more and better paying jobs in green energy. The Union of Concerned Scientists predicts that a renewable energy policy would create more than three times as many jobs as producing an equivalent amount of electricity from fossil fuels.

“Sometimes we in the Northwest think that we’re the only ones with this problem, but it’s not just us. They’re battling the shipment of tar sands oil through New England. They’re fighting the Cove Point terminal in Maryland, fracking in Pennsylvania, and tar sands oil in Utah,” she says.

Bonnie tries to warn people about a fossil fuel project here that hasn’t gotten much attention. It’s a small asphalt plant in Northwest Portland near the Willamette River recently purchased by Arc Logistics Partners, LP, which owns fuel plants throughout the East and Midwest. According to Arc Logistics’ CEO, Vince Cubbage, the Portland facility is poised for growth. Opponents like Bonnie are deeply concerned that trains carrying Bakken crude have been exploding regularly, and that routing these trains through the heart of Portland is a terrible idea. As of last September, the Climate Action Coalition has taken on this battle with Bonnie’s support. This is a coalition of groups willing to confront authorities with nonviolent direct action, meaning that they would put their bodies on the line if necessary. All of these groups are dedicated to nonviolence, but they’re ready for confrontation.

There is no doubt that Bonnie enjoys these community efforts, especially when she can see the impact. Back in 2012, when Montana’s governor was promoting the opening of the Otter Creek Land Tract for strip-mining coal, a group called Blue Sky Montana organized a civil disobedience action. Gov. Brian Schweitzer told them, “Nothing you can do will change my mind.” So Bonnie traveled to Helena where she participated in a weeklong action at the Capitol.

Her face lights up when she describes the scene: “It was fantastic! We were so supported. The custodial staff at the capitol hung our banners in the rotunda! We had an all day teach-in right there in the Capitol. At the end of the day the building was closed and we were asked to leave, but quite a few of us stayed. Altogether, 23 people were arrested for trespassing. Sixteen of us pleaded not guilty on the basis of an old law, ‘The necessity clause.’ If the case would be tried, our defense would be that it was necessary to stay there.” As it turns out, The Otter Creek Mine has yet to be opened.

Bonnie explains the necessity clause: “For example, if a house is on fire and you run in to grab a child, you may be trespassing, but your action is necessary. Well, this is how it is: there’s a fire in our house and it’s called climate change.”