April marks the debut of the Portland Baroque Orchestra’s newest member: the Ruth Rolt fortepiano. Its player is Eric Zivian of the Benvenue Trio, whose other members are violinist Monica Huggett (also PBO’s artistic director) and PBO cellist Tanya Tomkins.

The fortepiano brings an important addition to Oregon’s music scene. It’s a rarer — and to many ears, more precious — keyboard instrument than its modern successor. “If I had my way, they wouldn’t have extended the development of the piano past 1850!” Monica Huggett told Vancouver Classical Music. “A fortepiano or a period piano (such as an Érard or Broadwood) balances so well and allows all the primary colors of the music to surface.” And Zivian says the fortepiano has more character than the modern piano.

The Ruth Rolt fortepiano allows PBO to bring repertoire that Oregon has rarely heard before. For example, PBO will include in its next season one of Mozart’s last piano concertos played by Zivian on the Rolt fortepiano. This Friday, April 6, the Trio plus its new member will perform works by Mozart, Haydn, Hummel, and the Hungarian composer Józef Koschovitz at Portland’s First Baptist Church.

William Rolt and Portland poet Judith Barrington donated the Ruth Rolt fortepiano to the Portland Baroque Orchestra, in memory of his mother and her sister, respectively. Poet, memoirist, writer, and teacher Barrington, who could be considered the fortepiano’s aunt, is well known to the Oregon literary community, but not many Oregonians know about her late sister the concert pianist. You could say that love brought this precious instrument to Oregon — a pianist’s love for early classical music, for this instrument’s special qualities, and for Oregon.

Fortepiano or Pianoforte?

Loud-soft or soft-loud? Both terms originate from the 18th-century name, gravicembalo col piano e forte (harpsichord with soft and loud), referring to the new instrument’s ability to produce varying sound volumes depending on the player’s touch. For a while, devotees of the new piano, like Jane Austen, used the two terms interchangeably.

The fortepiano was the instrument on which Haydn, Mozart, C.P.E. Bach, and their contemporaries composed, and Mozart wrote a glowing letter to his father about the virtues of the Stein model.

By the 18th century, the fortepiano had evolved beyond the harpsichord in several ways. It employed hammers rather than plucking the strings. It also added a knee pedal (which later became a foot pedal) to lift the dampers off the strings and sustain the notes, and, in some cases, a “moderator” pedal, which puts a piece of felt against the strings, acting like a soft pedal.

In 1784, the German builder Johann Andreas Stein transformed the instrument. One of most innovative features of Stein’s fortepiano was its action, the mechanism that transfers the motion of the keys to striking the strings. Stein’s action was a complex system of levers and hooks, in which the striking end is located closer to the player than to the hinged end. This became known as the Viennese action and remained popular for many years. The result of the new action was a piano that was extremely sensitive to touch.

What makes the fortepiano sound so different — and to many ears better, at least in more intimate settings — than its descendant? Eric Zivian, a contemporary pianist with an affection for the older model, describes the action of the Stein fortepiano as very light with a more articulate feel. “The treble notes have a tinkly sound, and there’s a beautiful bass sound,” he explains, mainly due to differences in construction.

The modern piano’s strings are wound around a big metal frame, or harp, creating considerable tension and a louder sound. The fortepiano’s wooden frame and looser strings allow faster decay and less resonance. As a result, the sound is generally quieter and more articulate. In addition, the fortepiano’s strings do not cross as in today’s piano, but run lengthwise the entire way so that there is less resonance, but what Zivian describes as a purer bass sound. “And it’s easier to play fast!” he says. “Even to play loud, there’s not as much athleticism involved as with the modern piano.”

Because of its softer, less resonant sound, the fortepiano blends well with bowed, gut-stringed instruments like the violin and cello. “In the modern piano trio,” Zivian explains, “it is often very difficult for the piano to keep from being dominant.” Trios by Haydn and Mozart and even later composers therefore sound quite different when a fortepiano is used.

Renowned pianist Kristian Bezuidenhout and tenor Mark Padmore praise the fortepiano’s “conversational tone” and its role as collaborator in a recent article in BBC Music Magazine. Using Schubert’s lieder as an example, Bezuidenhout states, “There’s a beauty of sound and a range of soft and loud that’s possible on the instrument which the composer would recognize. The orchestral effects that Schubert produced are impossible to replicate on a modern piano.” If you’re listening to chamber music including a piano by composers before, say, Liszt, you’re not hearing exactly what the composer intended unless it’s played on a fortepiano.

Ruth Rolt Meets the Fortepiano

Ruth Barrington Rolt, born in England in 1933, attended the Royal College of Music, where she studied with Arthur Alexander and earned an award for her interpretation of the music of J.S.Bach.

“It was very sexist,” in those days, Barrington reports. “They told her she shouldn’t try to play orchestral concertos because she was a woman and she wasn’t strong enough. She was actually tall and quite strong, but she didn’t want to do that anyway.”

Rolt loved Bach and the early classical period, and she loved chamber music. She played piano, harpsichord, and fortepiano in a variety of venues, including as a repetiteur for an opera company.

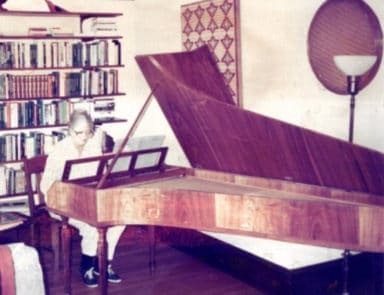

When Rolt’s husband Peter retired from his job as an oil company executive, the two decided it was the right time for Ruth to have her dream piano. They commissioned the London piano maker Donald Mackinnon to build a copy of the iconic Stein fortepiano, which he delivered to the Rolts in 1987, and Ruth described it in a letter to her sister as “ravishingly beautiful” with a “marvelous sound.” The retired Peter Rolt became expert at tuning it. His wife learned the repertoire of early classical composers and played it every day. She and her friends in Sussex started a group called Now and Then, which played both old and new music.

“She just fell in love with that fortepiano,” recounts Barrington. “I used to go to England every year and stay with her. We could make plans only for the afternoon because she played the fortepiano all morning. That was what she did.”

From England to Oregon

Ruth Rolt had an adventurous spirit, so when Barrington suggested in 1990 that she make a visit to Oregon with her new favorito, Rolt replied, “Why not!” Barrington became the impresario and arranged concerts for her in several Northwest venues, including Eugene, Corvallis, Bend, Joseph, the Maryhill Museum in Washington, and a concert at her own house in Portland that featured duets with tenor Scott Tuomi, who lived nearby.

When it was time to ship the instrument from England to Oregon, Peter Rolt built an elaborate crate for the fortepiano with little compartments where they stowed the legs and all the clothes they would be needing, which served as padding. The crate was so big that Rolt told her sister in a letter, “If you decide to take the piano out, you could live in it.”

The instrument survived the Atlantic voyage and the cross-country journey, then sat in Judith’s front yard for several days until Peter, Ruth, and their sturdy 19-year old son Daniel arrived to open the crate and bring the fortepiano indoors. Fortunately it was early summer and the weather was favorable.

For the recital tour, Barrington rented a 12-seater van and took out most of the seats to make room for the fortepiano. She had written contracts that specified assistance in loading and unloading, and required a minimum of four hours for Peter to tune the piano. They set out driving east on the Washington side of the Columbia Gorge. Barrington remembers that Ruth and her family were “totally buzzed” because they had never been to the western U.S. before. “They kept saying, ‘Look! There’s no houses! Where will the people come from?’ It was like we were out in the middle of nowhere. But sure enough, we got to Maryhill, and at the right time a lot of people showed up. It was beautiful!”

The concert at the Maryhill Museum was a highlight, with its big windows looking out onto the Gorge and Mt. Hood. Another was Joseph in Eastern Oregon, where the family from England sat in a cafe eating a huge American breakfast, awed by the spectacle of Canada geese landing on the lake outside the window.

Everywhere the local arts councils and other presenters hosted them enthusiastically. During the concerts, Rolt would speak to the audience from the keyboard about the composers and their work and about her beloved fortepiano. After the tour, the family packed the instrument in its custom crate and shipped it back to their home in England, where Rolt played it faithfully for twenty more years.

Ruth Rolt died in 2015 at age 82. Judith knew that she would have been delighted to have her fortepiano come back to Oregon, and especially to make its home with the Portland Baroque Orchestra. “It seemed like a real dream to have it come here,” says Barrington, “rather than just to be sold to somebody.” This way it is returning to the land of Ruth Rolt’s American adventure and to a family that will cherish it and display its charms to an appreciative audience.

1 thought on “Benvenue Trio preview: Viennese action”

Fascinating article. I hope to hear it one day!