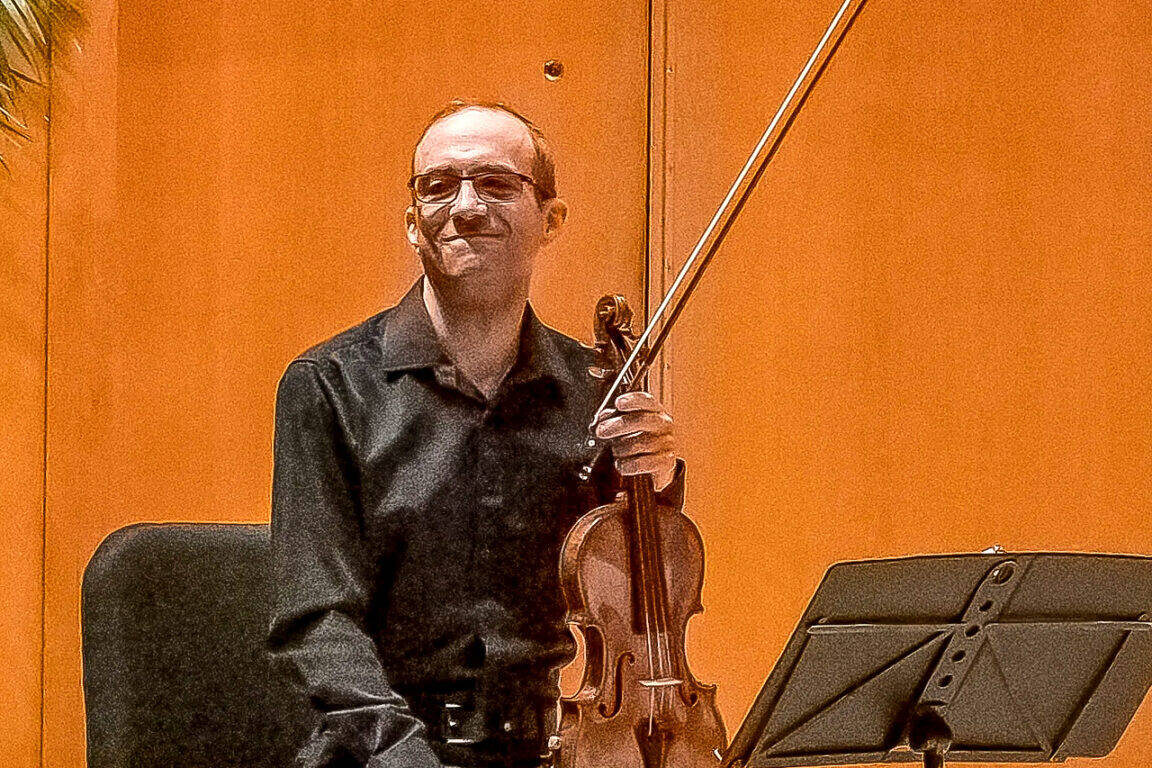

As Chamber Music Northwest’s resident ensemble for the 2021-2022 season, the Brentano String Quartet gave two concerts in July before the heat dome arrived. Shortly before the concerts, we spoke via Zoom with the Brentano’s first violinist Mark Steinberg about the quartet’s longevity (31 years), his approach to music making, and their most recent collaboration with soprano Dawn Upshaw.

Post Covid

As they have been for so many artists, the pandemic years were difficult and lonely for Steinberg. The Brentano didn’t play as a quartet for several months, although they sometimes went for walks together, but they finally decided that even if they had nothing planned they would still rehearse. “Honestly,” Steinberg reports, “the thing that was the hardest for me was the period when we were not playing quartets together. I even feel that when we’re on stage, that it’s more about playing with each other than about performing for the audience.” He assures us that it’s not that the audience is excluded, but it’s more like they get to eavesdrop on what’s going on with the Quartet. The intensity is inward within the group rather than directed outward.

The Brentano did some streaming for various presenters, but Steinberg didn’t actually watch any streamed concerts. “I stayed away from that. It was painful,” he admitted. But now he says it’s wonderful to be back in the same room together, sharing the same vibrations more directly. He doesn’t seem to be bothered by the fact that significant parts of the faces in the audience are hidden by masks, and he actually appreciates their effort to keep everyone safe. Nor does he mind wearing one himself. One member of the Quartet was masked during the recent July 23rd performance. It is clear that their ability to communicate with each other is much more complex than just through facial expression.

Staying fresh

Last year the Brentano celebrated their 30th anniversary. Such a long time together has significant advantages in evening out rough places and building solidity, but there’s always the danger of complacency. Steinberg’s response to this question was to tell how they began their very first program with Haydn’s Op. 71 No. 2, which has a challenging opening. “It starts with this big orchestral chord, then a very intimate response, and it takes a lot just to get the right effect. So here we are, 30 years later and still working on it!”

Steinberg reports that it’s an ongoing preoccupation, that the Quartet always wants to feel they’re offering something fresh and engaging in the moment. Not only does he want to avoid complacency, but he is learning how it’s possible for a group to play together and yet for all the members to feel free while doing it. “There are competing demands – the demand of ensemble work and the freedom to do what you want. It’s something that I think about constantly.”

The case against simultaneity

Quartets are often judged by the success of their ensemble playing, that they seem to play “as one.” Steinberg challenges that notion. He believes that the way chamber music groups try to play together sometimes “stiffens” the music making. He is passionate about the subject:

I think there’s something very strong in the chamber music culture right now which says that the moral center of what we do concerns simultaneity, the vertical alignment of the parts, and if that’s not there nothing else is worthwhile. I find that misguided and problematic, partly because it’s often very beautiful when when the parts don’t align vertically, and, in my opinion, it’s not always what’s called for by the way the composers write. There are moments when it’s very important and moments when it is not.

Steinberg believes that this emphasis on vertical alignment is a relatively new way of thinking and there may be cultural reasons for it–like the recording process, where the repetition of non-simultaneous instances could become annoying. But he brings out examples of old quartets, like the Flonzaley, the Capet, and the Busch quartets where he hears a lot of non-simultaneity. Also pianists, from those who long ago studied with Clara Schumann all the way up until recently. “I mean you can hear Bartok playing his music and very often the hands are not together. It’s certainly not for lack of ability — it’s a different aesthetic. Sometimes it makes for more clarity and the counterpoint has more meaning.” He favors a “scaffolding or structure that is more flexible, within which you can maneuver and within which surprising things can happen.”

Interiority and revelation

For the first half of their July 23rd concert with Upshaw, the Brentano presented a medley of songs and instrumental pieces from the Renaissance and Baroque periods, which Steinberg, in his eloquent program notes, calls a blending of “interiority with revelation, a clarity of vision melding the rational and the instinctive” (read our review here). Because the music of that period was played in the living room rather than the concert hall, he likens it to a conversation among friends, on which the audience may eavesdrop. He points out that this music was not intended for string quartet, but for their ancestors, consorts of viols, and for the human voice. The influence of the body is also evident through the medium of dance, as in Locke’s courante and saraband or elements of dance in Purcell’s fantasias.

For those who may think that Baroque music lacks emotion, Steinberg’s opinion is quite the opposite. He describes the way in which the contrapuntal lines “collide and twist around each other” as representing the friendliness and frictions of human relationships, and sometimes the tragedy. He particularly loves Purcell’s Fantasia No. 4 in C minor, which he says he could play every day for the rest of his life without ever getting tired of it. “These lines clash into heart-rending dissonances, and you expect that it will release into consonance. And instead, what happens is that one of the parts comes around the other side and hits it again, and goes into a stronger dissonance before it finally lets go. It’s completely shocking!”

Inherent in this view of music is the necessity of accepting ambiguity–the holding of opposites–which Steinberg believes is one of the richest things in music. But he maintains that there is a rupture between then and now in one important way – that none of this earlier music was intended to be played as a performance, but instead to be played at home. “It was like being in a salon together — there was an art to it, the art of conversation.” The break with that music came with Haydn. While Haydn’s earlier quartets were very much in that vein, the quartets later in his life were intended for the concert hall. “I think that’s an essential change that we’ve never gotten back from. That’s not to say that there aren’t elements of interiority and intimacy in later music. There absolutely are, but the flavor is different.”

Collaboration with Dawn Upshaw

The Brentano has collaborated several times before with the celebrated soprano, Dawn Upshaw — in Schoenberg’s Quartet Op. 10, No. 2 and Respighi’s Il Tramonto, based on a poem by Percy Shelley. Her impressive resume includes not only acclaimed performances on the opera stage and concert hall, but she is the first vocal artist to be awarded the MacArthur “genius” prize. She is loved by audiences of all ages.

According to Steinberg:

Dawn is one of the great singers of our time. There’s a frankness, a directness, a sincerity of expression in whatever she does that I find incredibly moving, and she’s a great chamber music partner. She listens beautifully. She can float above the quartet and she can blend into the quartet. Sometimes it’s a singer plus quartet and sometimes it’s a quintet.

After performing Il Tramonto at the 92nd Street Y in New York, the Brentano was encouraged to come up with something new with Dawn Upshaw. At that point Steinberg had a memory of being enraptured by Jessye Norman singing Schoenberg’s monodrama Erwartung at the Met Opera and thinking that it would be wonderful to have a monodrama partnering with Upshaw. Reviewing various historical characters Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas came to mind and specifically the famous lament for soprano and strings. The plan was to put together a mix of English vocal and instrumental music for the first half of a concert culminating in Dido’s lament. Selecting for the opening piece Purcell’s Oh Let Me Weep from the Fairy Queen, with its recurring base line so similar to that of Dido’s lament, would provide bookends for the first half.

Dido Reimagined

The Brentano members decided enthusiastically on Melinda Wagner as the composer of the new monodrama, who then turned to Stephanie Fleischmann for the libretto. Wagner is a well known contemporary composer who received the Pulitzer Prize in Music for her Concerto for Flute, Strings and Percussion and currently chairs the Department of Composition at the Juilliard School. Playwright and librettist Fleischmann’s works have been performed throughout the U.S. and internationally. Instead of a lovesick suicide for the great Queen, Fleischmann and Wagner have composed a reimagined script for a modern heroine, consisting of solitude, returning to nature, and healing. https://open.spotify.com/embed/album/2dYnFPlX4ElrHndouHQ1BL?utm_source=generator

In addition to Chamber Music Northwest, Dido Reimagined was co-commissioned by six other presenting organizations. The presentation in Portland on Saturday, July 23rd was its West Coast premiere.

Future plans

The Brentano will continue to play quartets! They also have a new viola quintet written by Scottish composer James MacMillan and another piece in the pipeline by Lei Liang. The Lei Liang commission comes out of a long term friendship between the Brentano and Liang’s composition teacher, the late Chou Wen-Chung, promoter of Chinese music and godfather to a generation of Chinese composers, such as Tan Dun, Chen Yi, Zhou Long, and Bright Sheng. In the 1980s, when Wen-Chung was already in his 70s and had never written a string quartet, his students secretly shopped around for just the right group to play such a quartet.

When they discovered the Brentano at the quartet’s debut concert in New York, they opened a communication line between the aging composer and the young Quartet. As a result Wen-Chung wrote two quartets for the Brentano. When he died, his family made a financial gift to the Quartet, which they, in turn, will use to commission a piece from Wen-Chung’s student, Lei Liang.