Hold These Truths is a drama for our time. Set amid the turmoil of America’s entry into World War II, Jeanne Sakata’s one-actor show is about the struggles of the civil rights hero Gordon Hirabayashi, a young student at the University of Washington, to reconcile his passionate belief in the U.S. constitution with the infamous betrayal of Japanese Americans during the war hysteria after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

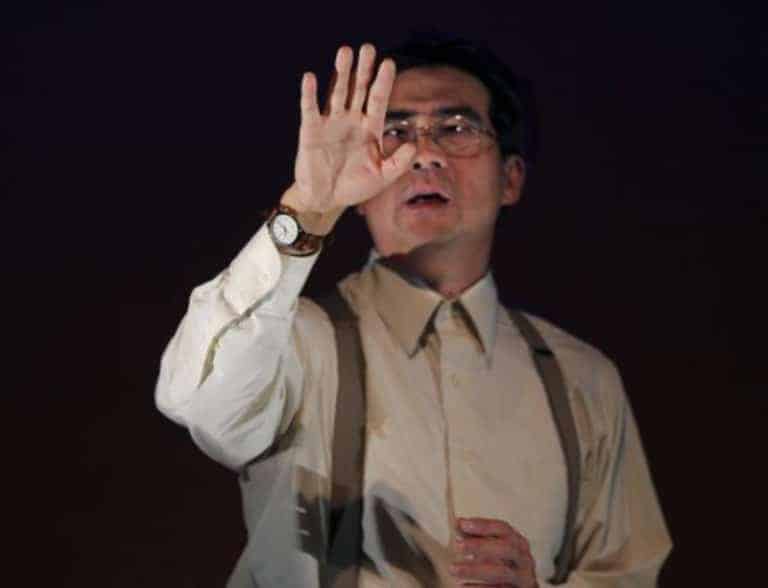

Sakata’s play – which comes, she says, at a time when racism and anti-immigrant hysteria are again on the rise in America – begin previews on Sunday and opens Friday, October 8, in the downstairs Ellyn Bye Studio at Portland Center Stage. It stars Ryun Yu, who also played the role a year ago at Seattle’s ACT Theatre and in its 2007 world premiere at East West Players in Los Angeles, both times directed by Jessica Kubzansky, who also directs in Portland. Hold These Truths debuts Center Stage’s Northwest Stories series, which will continue with three more shows this season: The Oregon Trail, by Bekah Brunstetter; Astoria: Part 1, Chris Coleman’s new adaptation of Peter Stark’s book; and Wild and Reckless, a new show from the musical group Blitzen Trapper.

Jeanne Sakata, whose first name is pronounced “Jeannie,” is also an accomplished actor who received accolades several years ago for her performances at Portland Center Stage in David Henry Hwang’s M Butterfly and Chay Yew’s Red. She went on to star in a variety of plays all over the world, as well as film and TV shows. She has been called a “local treasure” by the L.A. Times.

Knowing that Jeanne was Japanese-American, I requested an interview. I had good reason.

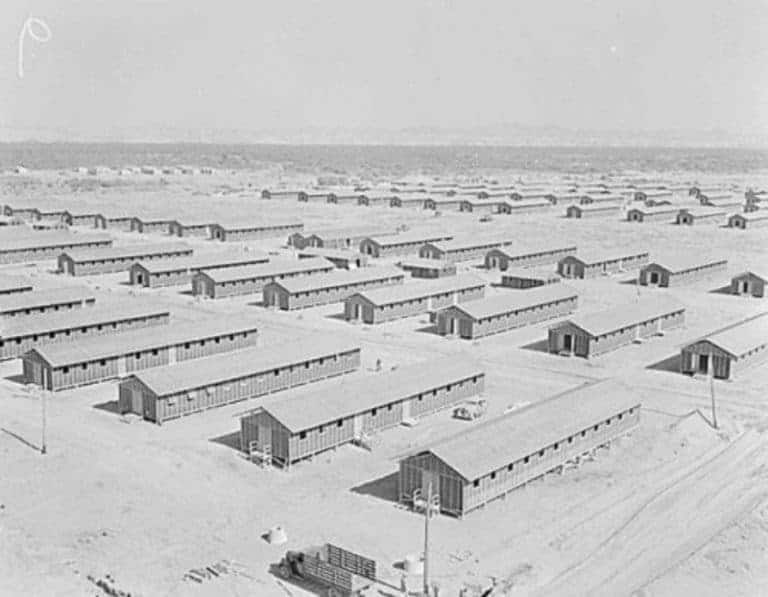

I HAD RECENTLY RETURNED from a pilgrimage to the Heart Mountain World War II Confinement Center, a concentration camp known in euphemistic terms as a “relocation center.” When I was five years old I had spent an idyllic summer at a ranch outside Cody, Wyoming, where my father had a mysterious job. It was 1942. Some 30 years later I found out that my father had been an architect and construction supervisor for the hastily built Heart Mountain camp. In the fall of 1942, not long after my family returned home to Illinois, nearly 11,000 persons came to live in the Heart Mountain camp. They had been forcibly uprooted from their homes on the West Coast, taking with them only what they could carry. My father and I never discussed the subject.

For some time I had thought about making a pilgrimage to the Heart Mountain site to pay my respects to the ghosts of all those people living in the prison my father had helped to build. But until recently, there was nothing there. Now, however, there is a comprehensive interpretive center and an annual event with speeches, banquets, and activities for former incarcerees and their families, as well as other interested persons like me. So this year I decided to go. It was an unforgettable experience.

While I was nervous about the reception of my story, I was greeted with interest and enthusiasm, as if people were grateful that I had made the effort to come and hear their stories. I learned a great deal about the appalling treatment of those people by the U.S. government, ignoring their constitutional rights and locking them up without due process for no crime, but because of their Japanese heritage. It was all the product of racism, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership. I came away in awe of their courage and resilience, and their ability to forgive.

WHEN I CALLED JEANNE SAKATA I told her how I had gotten tickets the minute I heard about her play. I also told her of my interest in the story of the Japanese American incarceration, with just a bit of the nervousness I had felt on arriving at Heart Mountain. Not necessary. Her voice was warm and clear, and within minutes I felt as though we could be friends. Right away I asked if her parents or relatives had been sent to one of the ten camps.

“Yes,” she said. “My father and grandparents were in Poston [southwestern Arizona], along with my uncles, aunts, and cousins. My father was in high school at the time and my aunts and uncles were probably college age.” Jeanne’s mother’s family, however, had lived in Colorado. Not being residents of the West Coast and therefore not a supposed “military threat,” they were not forced to leave their homes. “Later,” she said, “when my mother’s family found out about the conditions in Poston they were shocked.”

I asked Jeanne about why she chose the topic of a Japanese American college student who fought for his constitutional rights. It was her first experience as a playwright.

“I’ve always been a proud member of the Asian-American community. As an actor I started out with the East West Players. Then one day I saw a documentary by a filmmaker named John de Graaf called A Personal Matter: Gordon Hirabayashi vs. the United States. It was the first time I had ever heard of Gordon, and I think that because of my family’s background and their experience with the camps I had a great psychological need to know more about Gordon’s story — his story of resistance, his reasons for challenging the curfew and the exclusion orders.”

Fortunately Gordon Hirabayashi was still living at that time and Jeanne was able to interview him twice, once at his brother’s home in California, and the second time at his home in Alberta, Canada. Interestingly, she did not find out much from her own family about the Japanese American experience of the exclusion orders or about the camps.

“It’s not something that was discussed in my own family — ever, really. I would ask questions here and there, but I would either get cut off or the subject would change very quickly. But I always knew that there was some reason why they weren’t discussing it. I couldn’t have articulated it at the time, but I knew there was something there that was really important.”

Occasionally her relatives would bring up bits of stories:

“I remember a couple of my uncles telling me about my uncle Tosh who saved and worked and worked to buy a car. He finally bought a used car and was so proud of it. Then the orders came out [to evacuate] and he had to sell it. There were stories like that in the family. My aunts would say how dirty, how filthy the camps were. But no one really told me extended stories, and I think that’s where interviewing Gordon filled a great need within myself to hear stories about this period, to digest it all and to work it through.”

When I asked why her family cut her off every time she brought up the subject, Jeanne paused for a moment.

“I think it was just way too painful to talk about it. It wasn’t a feeling just in my family but in all Japanese American families. They wanted to put this all in the past. They wanted to move on. But of course, psychically those painful memories always stay in your subconscious and fester there if they’re not addressed.”

We talked briefly about the reparation hearings. In 1980 President Jimmy Carter had established the Commission on Wartime Relocations and Internment, and survivors of the camps came from all over the country to testify in the hearings. Understandably, emotions were running high.

Jeanne explained, “I think when you saw those hearings, and the Japanese Americans testifying about their experiences in the camps, that’s why you saw so many of them break down and cry. They had been silent for so long and they had tried to forget and stuff it down, but all these feelings came pouring forth.”

On April 26, 2012, President Obama awarded Gordon Hirabayashi posthumously the Presidential Medal of Freedom, along with several others for making a lasting contribution of the life of the Nation — for challenging us, inspiring us, and making the world a better place. I asked Jeanne if she knew what had inspired the President to give the medal to Hirabayashi.

“I think the man that greatly contributed towards President Obama awarding Gordon the Medal of Freedom was former [acting] Solicitor General Neal Katyal, who took Elana Kagan’s place after she went to the Supreme Court. When Neal Katyal was a law student he was very inspired when he learned about Gordon Hirabayashi, and Gordon became one of his heroes. When he became [acting] Solicitor General, Katyal saw a chance to right this historic wrong.”

Hirabayashi’s case had gone all the way to the Supreme Court. In arguing the government’s position, then Solicitor General Charles Fahy, against the advice of his staff, suppressed evidence that would most likely have overturned his conviction by a lower court. Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal spoke openly about it in a moving tribute in the Washington Post. For the first time, the U.S. Justice Department issued a public confession of a lapse in ethics.

Did he see the play, I asked?

“Yes. Neal Katyal came to see the New York show in our off-Broadway production of Hold These Truths, where he graciously did an audience talkback for us. He told us about how he had recommended to President Obama that Gordon received the Medal of Freedom for standing up for the constitution during WW II.”

FINALLY, I ASKED Jeanne if she saw any similarities with today’s environment.

Another pause. “Well, even in Gordon’s time the second generation, my parents generation [the Nisei], of which Gordon was a part, didn’t believe that anything would happen to them because they were American citizens. So they were plunged into shock when they learned that the government intended for them to be in prison as well. And I think that what we have to remember is that we’re never really safe. Racism is unfortunately very much on the rise. It’s running rampant right now because of the Trump candidacy and the anti-immigrant hysteria that he’s whipping up. Hate crimes against Muslims and Muslim Americans have risen significantly and alarmingly. So if anything, I’d like the play to serve as a beacon of hope in terms of Gordon’s story and his ultimate vindication. It also shows that we in the minority can never really take our freedom for granted. Like the Nisei, we think this is not going to happen to us, but we really don’t know. We can never really take our liberties for granted. I think Gordon’s story is one that every American should know.”