Chapter 14 of my book, An Uncommon Cancer Journey, describes a memorable side-trip to an art center in Germany, right before Jack’s mega-dose of chemotherapy.

Once he was well, Jack would say repeatedly that beauty was one of the most important ingredients of his healing. He didn’t wax poetic over sunsets, birds, or flowers, although he did take a course in Ikebana (Japanese flower arranging) much later. He was not a 19th century romantic. He often forgot our anniversary (but actually, so did I), and he rarely brought me flowers. When he did it was usually something he picked up at Safeway because it was my birthday or because I had complained about how he never brought me flowers.

Jack and jazz

Jack’s loves were art and music, specific kinds of art and music. He loved jazz, but it had to be pre-1948, the advent of Long Play records, which he maintained ruined the careful structure of “legitimate” jazz since they allowed much too much time for improvisation, i.e. doodling around. His tapes of classics like Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, and the Ink Spots were nearly worn out, but he had them on whenever he was working in his shop or driving his car.

The pull of visual art and artists

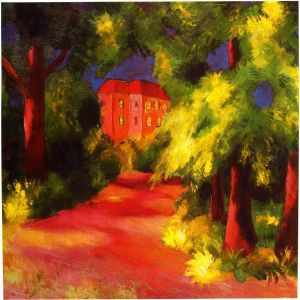

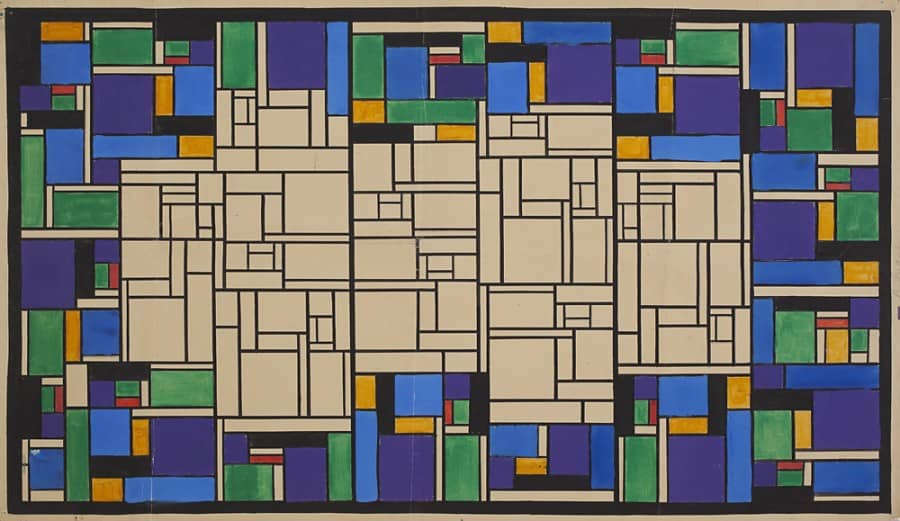

When it came to visual art, he liked most everything post-Renaissance, especially the Expressionists and those coming after. Whenever we went to a new city we would go straight to the tourist office, get maps, and locate the art museum. Once in the museum we would often separate, make the rounds, then show each other the pieces that particularly moved us. We would sometimes go back again before we left town. Jack’s taste was eclectic, although he tended toward the modern, especially the colorful.

Not only were Jack and I drawn to art, but we seemed to gravitate toward artists. While in Bonn for treatment at the Janker Klinik we made friends with two other American couples, and it happened that both of them were involved in the arts. Fanny and Rocky Hawkins were from Seattle. Fanny was being treated at the clinic, and her husband, Rocky was a western artist whose vibrant images have become quite popular over recent years. The other couple was from Los Angeles — John Phelan, an accomplished graphic artist, also being treated for cancer, and his partner Alvin Louis Wiehle, an architect and one time student of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Of course we visited the Kunstmuseum in Bonn more than once and fell completely in love with August Macke, another of Bonn’s famous sons, although his was not quite the stature of Beethoven. We bought a poster of Macke’s Rotes Haus im Park, which followed us for years every time we moved to a new house. We loved the brilliant, unexpected colors and flat perspective, characteristic of the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) School, of which Macke was a founding member, along with his more well known colleagues Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky. There is something very life-affirming about the Rotes Haus, as if the artist is daring us to see the world in his unconventional, joyful way. Macke died at the age of twenty-seven in World War I. Who knows what he could have done had he lived to old age?

Hopsital Art

Near the end of Jack’s treatment, the Janker Klinik moved him to a small private room while they administered the most powerful of the chemotherapy cocktails they had given him so far. Fearing that the tumor was getting out of control, they wanted to try their strongest weapon. What I remember most about that room was the picture on the wall above his bed. It was a reproduction of an old Flemish still life with a dead goose, head on its long neck lolling over the side of the table. And I remember thinking, What a bizarre way to entertain patients while they are receiving chemotherapy! If there is such a thing as anti-healing art, this must be it!

Years later, Jack and I thought up a scheme where we would try to get a grant for a pilot project in a hospital. The idea was to have lots of brightly colored reproductions of beautiful paintings — everything from the old masters, to the Impressionists, to the Expressionists, or even quite contemporary paintings. Everything from Vermeer to Monet, to Van Gogh, to David Hockney. When new patients were admitted, we would give them a choice of what they would like on the walls of their rooms while they received treatment. If they grew tired of a picture, they could change it for another. I’m sure that part of our motivation was the fun we would have in picking out the candidate pieces of art.

Graven Images Gallery

Instead of following up on the hospital art scheme, we opened “Graven Images Gallery” in Ashland, Oregon, where we carried fine-art prints and ceramics. Jack felt that the way to offer people the best art at the most reasonable cost was in the form of limited edition prints, such as woodblocks, etchings, and silk screens. The gallery was Jack’s baby, and he loved it. We changed the featured exhibit every month and we provided opening receptions with wine and cheese for the artists. The gallery business is tough in any city, even a cultured one like Ashland, so we eventually had to close. Jack had always said, “Graven Images Gallery was a critical success and a commercial failure.” But he maintained that in the process we brought a lot of beauty into people’s lives.

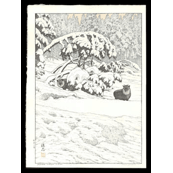

There are three large prints from those days that I have hung in my bedroom. I can see all of them as I sit up in bed, which is where I often meditate, write, or listen to music. Each piece has a special meaning as well as its own beauty. It’s not that I feel a great rush of endorphins when I look at them. It’s more like the quiet pleasure of acknowledging old friends, their gifts, and what we share in common.

Directly in front of me is a woodblock print by the Japanese artist Toshi Yoshida. It is a very quiet print in black, gray, and white, of antelopes in a snowy forest. Jack and I picked out this print together and I find it very peaceful. On my left is a woodblock print that I admired at an international print show in Portland, in 1997. As a surprise, Jack contacted the Norwegian artist, Eva Rydhagen, and bought it for my birthday (better than any bouquet of flowers). It is entitled “Courage,” and it depicts three penguins perched on the edge of a cliff overlooking the ocean. Two are awaiting their turns to jump, and the third is in a mid-air dive toward the sea. At first I hung it directly in the front as I sit up in bed, and, after deciding that my life already offered plentiful opportunities for courage, I placed it on the side wall where I could enjoy it whenever I wanted, but would not be continually confronted with its message.

On the right, and easily visible as you enter the room, is an etching by the French artist Claude Gaveau, an abstract still life in blues and greens called “Bouquet.” It is one of two prints we bought at Artes, the international print company we visited in October of 1985, shortly before we left Germany. Jack had just been given another dire prognosis — the tumor was rapidly growing back, and it was massive. Instead of collapsing in fear and dread, we decided to go art shopping. Now whenever I look at the Gaveau, I remember the day we traded despair for beauty, and I am reminded about the healing power of art.

2 thoughts on “The Healing Power of Art”

Your web site is exquisite, Alice.

Thank you, Ann – It took a while!