Dizzy

I had just finished a retreat in California that should have been restful but wasn’t. I had started out tired and overcommitted, and I spent hours struggling to stay awake during meditations. As soon as I arrived back home I started to prepare for another trip, this time for a whole month, with a departure date in five days. During that time I needed to review several scientific papers, arrange for pet sitters, do loads of laundry, and make various last minute preparations.

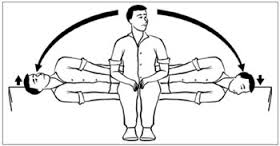

Suddenly I found that my sense of balance was completely out of whack. Moving my head made the world spin. I began to walk like a drunk, and I could hardly contemplate what to put in my suitcase. My doctor thought it might be benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, better known as BPPV, where tiny crystals in an organ of the inner ear migrate into the semi-circular canals, another organ of the inner ear, and mess up one’s sense of balance. Checking the internet and talking to friends lead me to some exercises called the Epley maneuver, which I began to practice in earnest. Reluctantly, I decided to cancel the first part of my trip, which included the scientific meeting that I so much wanted to attend, as well as a visit to some favorite friends in D.C., one of whom said that if my hair had been the color it used to be, he’d call me dizzy blonde.

As an audiologist I was quite aware of the irony of vertigo making me miss a meeting all about new discoveries in hearing science. But as a writer and a spiritual seeker, I was also aware of the metaphor. The frenetic pace of my recent weeks had thrown my whole system off balance. The metaphor was perfect — my world was spinning out of control and I was no longer grounded. Aside from the Epley exercises, there was nothing I could do except rest, seriously rest, which I did for the next five days until I was stable enough to fly to Baltimore and continue the remainder of my trip.

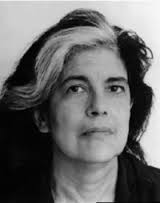

Susan Sontag

This experience reminded me of the book Illness as Metaphor by the American writer, critic, and political activist Susan Sontag, famous not only for her formidable intellect but for her outspoken and often vicious critique of other writers’ works as well as for the rapacity and ignorance of the Western world. Published in 1978, Illness as Metaphor is a polemic against what she perceived as the current practice of using cultural metaphors to describe serious illness. In the 19th century it was tuberculosis, and by 1978 it was cancer.

Sontag wrote the book while she was being treated for breast cancer, and she was clearly angry, blaming not the disease or treatment, but society for stigmatizing cancer patients with a shaming metaphor. She maintains that society regards cancer as a disease of the “psychically defeated, the inexpressive, the repressed — especially those who have repressed anger or sexual feelings….” (Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors, p.100.) She has particular contempt for any psychological theory that suggests the existence of a “cancer personality” or the tendency of some personality types to be more prone to developing cancer. She maintains that the concept of illness should be stripped of metaphor and understood in a strictly biochemical or physiological perspective.

Sontag states that the consequences of this metaphor are to inhibit people from seeking treatment early enough or to make people irrationally fearful of traditional cancer treatments and “foster credence in thoroughly useless remedies such as diets and psychotherapy” (p. 102) [emphasis added]. I found this a particularly disturbing statement since my husband Jack’s healing from “terminal” metastatic esophageal cancer, a much more dire prognosis than Sontag’s, included dramatic changes in diet and intensive psychotherapy, which he believed were critical to his recovery.

But Sontag rightly identifies the cancer metaphor of the time as a military one: The War Against Cancer, not unlike the War on Drugs. She also points out that society uses the same vocabulary as in warfare — cancer cells invade, radiation bombards, and the purpose of chemotherapy is to conquer or destroy. Ten years later, in her preface to the the section on AIDS, she notices that attitudes toward cancer had changed and it was treated less phobically. The stigmatization had by that time shifted to AIDS.

Who’s Afraid of Susan Sontag?

Not everyone has agreed with Susan Sontag’s assessment of the attitudes toward cancer, even back in 1978. In his article “Metaphor and Medicine: Narrative in Clinical Practice” (Yale J Biology & Med (2003) 76:87-95), Dr. Jack Coulehan believes that the use of this offensive metaphor was less common than Sontag claimed and that Sontag didn’t really explain how metaphoric thinking is harmful. It hasn’t inhibited the study of disease or treatment. Moreover, metaphoric or imaginative thinking is how we discover meaning in our lives, and since serious illness is an important life event, metaphor, like poetry and other forms of art, helps understand it.

Author and researcher Dr. Barbara Clow tested Sontag’s assumptions about the impact of cancer metaphors and found that during the first half of the 20th century the disease did not reduce patients to a state of silence or disgrace as Sontag purported (“Who’s Afraid of Susan Sontag: or, the Myths and Metaphors of Cancer Reconsidered,” Soc Hist Med (2001)14(2):293-312).

More than one of her fellow critics have pointed out that Sontag herself was not opposed to using the cancer metaphor when it suited her. In her 1966 review of a book about Genet by Jean Paul Sartres, she wrote, “Saint Genet is a cancer of a book, grotesquely verbose….” etc. (Against Interpretation and Other Essays, p. 93). A year later she wrote in the Partisan Reivew, “The white race is the cancer of human history.” (34(1):57-58) Despite her brilliance, it seems as though Susan Sontag was not only inconsistent, but a very angry person.

Cancer as Metaphor

In my book, An Uncommon Cancer Journey The Cosmic Kick That Healed Our Lives, metaphor is inherent in my story: the cancer journey, the labyrinth of illness and healing, and the cosmic kick. Likewise, Lawrence LeShan’s ground-breaking book, Cancer as a Turning Point and Jean Shinoda Bolen’s Close to the Bone: Cancer as a Soul Journey, which describes the experience as a mythical descent into the underworld. Also, the popular conferences for cancer patients and caregivers called Healing Journeys, organized and conducted every year by long-time cancer survivor Jan Adrian.

I continue to feel that the use of metaphor is very valuable to the understanding of illness. Like poetry, it uses words as symbols, connecting us to the meaning beneath the words, and giving more nuance to the condition. Understanding my vertigo as a metaphor for the topsy-turvy way I was living enabled me to see what I needed to do to heal — slow down, take a closer look at my life, and acknowledge the necessity of deep rest.

The thorny question that Sontag has raised about cancer and personality is a very delicate and controversial issue, and I have decidedly mixed feelings about it. Jack was quite clear that his lifestyle had contributed significantly to the development of his cancer, and I had to agree. Nearly 40 years of drinking, some of it hard drinking, had taken its toll on his esophagus, which isn’t designed for this kind of treatment. But more importantly, he experienced many years of repressed emotion after the death of his mother when he was seven and his father’s remarriage to a bullying stepmother. In more recent times he experienced the death of his eldest son, the break-up of his marriage, and the loss of his job through the firing of his boss, whom he had greatly admired. All of these events conspired to challenge his immune system, and he freely acknowledged their relationship to his cancer. Through intensive psychotherapy he was able to release and transform these emotions to the point where he told everyone that he felt blessed by his cancer! He called it his “cosmic kick in the ass.”

Like his healing process, and like Jack himself, this is all somewhat unusual. I know plenty of people who have or have had cancer challenges who have not had traumatic childhood experiences or even stressful experiences leading up to the diagnosis, who have not suffered repressed emotions any more than the average American, and who do not fit Susan Sontag’s description of the “psychically defeated” implied by the metaphor of her time. But Jack did fit this picture, and there are others who do.

Personality? Stress? Compromised Immunity?

One of the most influential books for Jack and me when we embarked on our journey in the 1980s was Getting Well Again by Carl Simonton, Stephanie Simonton and James Creighton. Written in 1978, the same year as Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor, its Chapter 5 is entitled “Personality, Stress, and Cancer.” If Sontag would have known about it (and she may very well have), she would have hated it. In their work at their Cancer Counseling and Research Center, the Simontons had seen many patients whose lives had followed a similar progression leading up to the diagnosis of cancer (pp. 72-75). The patients’ childhood experiences had somehow limited their resources for coping with stress. Then in adulthood these individuals had experienced “a cluster of stressful life events,” which threatened their personal identity. The patients were unable to cope with these stresses and felt trapped and helpless. The authors emphasize that this process does not cause the cancer but rather permits it to develop, and, of course, this is not a conscious choice on the part of the patient.

The Simontons proceed to describe the healing process. They maintain that as emotional states contribute to illness, they also contribute to health. First, patients develop a new perspective on life and on their condition. Just the realization of their own mortality can give them permission to change their behavior. Then, with the release of repressed feelings and the freedom to act differently comes renewed hope and the desire to live. Physical processes in the body begin to reflect these feelings of hope and renewed desire, resulting in the restoration of both mental and physical health.

In Cancer as a Turning Point, Lawrence LeShan discusses this process in a somewhat similar way based on his many years of experience studying and counseling cancer patients (pp. 24-25). He talks about how we all fall into traps as we navigate life, learning how to relate to ourselves and others. Sometimes these traps persist over a long period of time, putting intolerable stress on the body. He reminds us that we all have cancer cells in our bodies all the time. Some of these cells may “lose their coherence” with the body or a particular organ, our defense mechanism is weakened, and cancer results. The most powerful element in the process is the loss of hope that we can ever live our own life in a “meaningful, zestful way.” To counteract this process, Dr. LeShan’s own research points to the ability of our self-healing powers to raise our “host resistance” to the cancer by mobilizing one’s inner ecology and finding that turning point.

Distortions

Understandably, there has been push-back against these approaches to the development and healing of cancer. That’s one reason why the allopathic medical community gets apoplectic about the concept of “alternative” when applied to cancer treatment, and why “complementary” is a much safer word to use with your doctor. But there are also psychologists and other counselors who become indignant about the idea that patients may have played a role in the development of their cancers.

Psychologist Ruth Bolletino refers to “toxic myths” sometimes held by cancer patients or their families: that patients did something to cause their cancers, or that they had some kind of physical, emotional, or spiritual defect, that their attitude was not positive enough, or even worse, that it was some kind of punishment from God. These kinds of attitudes make me indignant as well. Blaming the victim does nothing to help and is often hurtful, both mentally and even physically.

In her book, How to Talk with Family Caregivers About Cancer, Dr. Bolletino reminds us that cancer is caused by a combination of genetic, environmental, and psychological factors. She acknowledges the contributing roles of smoking, alcohol, and sun exposure, and that changing lifestyle can change the environment in which the cancer grew, improving the likelihood of getting well. She maintains that it is not necessary to believe that we caused the cancer to believe that we can do something to change its progress. Dr. Bolletino quotes writer, poet, and social activist Audrey Lorde from her 1980 book, The Cancer Journals:

The idea that the cancer patient should be made to feel guilty about having had cancer, as if in some way it were all her fault for not having been in the right psychological frame of mind at all times to prevent cancer, it’s a monstrous distortion of the idea that we can use our psychic strengths to help heal ourselves. (Lorde, p.74; in Bolletino, p. 57.)

Another of Dr. Bolletino’s “toxic myths” is that the cancer patient needs to maintain serenity and a positive attitude at all times. This is another of the frustrating distortions caused by “New Age” thinking and pop culture. I would imagine that both the Simontons and Dr. LeShan would agree with the toxicity, even the stupidity of this statement. In fact, a key element in the psychotherapy that both Jack and I experienced during the healing of his cancer was the release of repressed emotion, and that doesn’t always look pretty.

Metaphor as Reminder

But we shouldn’t let these kinds of distortions invalidate the kinds of healing methods the Simontons and many other contemporary healers have developed. Delving deeply into the stresses and emotions that may have lead up to the diagnosis of serious illness can be of great value. The idea is not to blame, but to benefit from this knowledge and to release any obstacles to healing, knowing that psyche and soma are intimately connected.

If I hadn’t viewed my vertigo as metaphor, I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to connect it to my frenetic lifestyle and shift to a healthier way of living. The challenge is, of course, for someone who rather likes the fast lane, someone who always wants to squeeze the juice out of every moment, to actually make that shift. For that challenge, the metaphor is a powerful reminder.

16 thoughts on “Illness as Metaphor”

Fascinating. It seems as though the value of applying metaphor depends on who’s making the metaphor. Is it imposed from the outside and applied with a broad brush that disregards individual circumstances, or is it used by someone directly affected as a means of gaining insight into those individual circumstances? I suppose another question is whether the person affected is really generating her own metaphor or adopting one created from outside, like illness is punishment for sin or something.

Do I spy the seeds of your next book?

Good questions, Brett. Certainly imposing it from the outside and disregarding individual circumstances sounds like asking for trouble. But what if the patient doesn’t see the metaphor at all? Or sees a toxic one? That’s why counseling is so important, and good counseling at that. I wouldn’t want to be counseled by a fundamentalist preacher.

As for the next book, hmm. Hadn’t really thought about that, but….

Brett, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about my next book. I’m intrigued by the fact that so many big-time cancer centers, and even many of the small-time ones, are adding programs for complementary treatments as an adjunct to the usual chemo, radiation, and surgery. Mind you, not “alternative” ones, perish the thought, but things like diet, exercise, acupuncture, counseling, and meditation. They even use the word “spiritual” sometimes, although most likely in a churchy rather than a woo-woo sense. What has caused them to make these changes? And how has it been going? What and who are the obstacles? Is it so they can control what the patient ingests and does? Or do they really accept the healing nature of these practices? What do you think?

Good processing in order to “see” oneself, Alice!

The Lorde quote disagrees with Dr. Joe Dispenza’s book You Are the Placebo on epigenetics and changing our cells through our mind. There are many, many examples of reversing many illnesses. He is another source I’m appreciating right now.

Marie, are you maybe misunderstanding the Audrey Lorde quote? I think she favors the idea that we can use our psychic strengths to heal, but imposing guilt on the cancer patient for not having the right attitude and therefore causing the cancer is a distortion of that notion.

Another great post Alice! You are continually doing such important work! First and foremost it’s the inner-work that changes things through it’s outer expression. Symbols and Metaphor are potent transmitters to the unconscious that can be as broad as having collective meaning or as focused to mean something to just ourselves. The awareness does need to be one of exposing and mitigating anywhere a symbol or metaphor is used to blame, guilt, or shame.

Spoken (written) by someone who has given a lot of thought to the symbols and metaphors of our lives. Thanks for your insights, Angela.

A post-hospital visit to a Gastroenterologist who had attended me during my recent hospitalization offered a new view of myself. She sang praises to how good I looked and how positively things were progressing as we talked. Then in reflecting back on some of the critical moments in the hospital she said you were so stoic throughout the experience. I looked at her with a sense of befuddlement. She had not been present for some of the more extreme moments, and I wondered if she would have felt differently if she had. Her words continued to resonate for me after I left the office. As the days went by, my awareness opened and I saw it clearly. She had me pegged. I could see the threads throughout my life. Suddenly I was at liberty to choose something else. My new motto is: “Ditch stoic perseverance”.

I view my illness as a gift. I chose to enter into it deeply. Buddhism offered the healing remedies that brought me to a fuller understanding of myself. I still am in the recovery phase, but have hope that at some point life will resume normalcy. I find contentment in taking my time. Self compassion is a priority. I’m quite good now with aging and not knowing what comes next. I’m especially focused on improving communication with my family and friends. I find that mindfulness, insight meditation, keeps me aware of those little pitfalls that happen everyday inside my brain. I can’t change what has happened in the past, I can only pay attention to what is happening now. I don’t believe that long-term therapy would have been useful for me at this stage of life, but having been a therapist I know that it is powerful and transformative. We find what we need to get well, if we become clear that we want to get well. As you know, Alice, wellness can come from many sources.

Norine, thank you for that wonderful story! I just love it, “Ditch the stoic perseverance!” We could all use that kind of reminder, at least I know I could from time to time. And maybe that’s what the metaphor of illness is often about. I think you should send these paragraphs to your doctor, or maybe send the whole thing to your doctor, blog post and all. Doctors need more feedback — they need to hear more of this kind of thinking.

As an anthropologist, the idea that metaphor is inappropriate in describing illness is non-sensical. Every culture conceives of illness in its own ways. In the West, we tend to be physiological in our explanations, making allowance for the psychological too. Metaphysical explanations are pretty taboo. Not so in many places I work (Brazil, West Africa), where the source of illness might be a malevolent genie, an imbalance in an exogenous spiritual world that spills into the physical world, the doing of divine justice or black magic, fate, or any number of other explanations. These cultures usually don’t deny the physical manifestation of illness, but they explain its source very differently which cascades inexorably into the cures possible. Are these people misguided? Have only a handful of leading western hospitals and clinics stripped away all that unhelpful, distracting metaphor to get at the true essence of disease? I doubt it. The latter have succeeded in isolating a part of illness – the physical – and address it with zeal, skill and tunnel-vision.

From an anthropological perspective, for Western society or anyone to say it views an issue without metaphor is complete rubbish. Any word, for example, is a metaphor or symbol for something outside the head that thinks that word. Metaphor is the only way we understand reality, which itself is a strange concept since it posits the existence of “unrealities” in opposition to which reality can exist.

Let’s all relax and accept metaphor and symbol are everywhere, and without them we’d not be conscious.

Well said, Jamison. Actually, our “culture” is a bit primitive in this regard, isn’t it? All that zeal and tunnel vision directed toward slashing and burning….

Alice, what a thoughtful and stimulating article! This topic needs so much more exploration, and you have done a fine job of beginning the discussion. Your next book?

As someone who walked through a serious bout of cancer and came out the other end cured, and oh so changed, I greatly appreciate your thoughts on this topic.

I absolutely believe illness can be a metaphor for deeper understanding of our complex, often hidden, and rich lives. But this is an inside job, and must originate from the individual’s experience, and not some outer source.

For me, cancer provided an opportunity for me to STOP, reflect, reassess, renew. I chose to treat it as a life-changing time to learn more about myself, explore my “dis-ease” with my life up to that point, and find wonderful parts about who I am and my “core” beyond my physical body. I did not, and still don’t, describe myself as a “survivor,” or someone who “fought cancer.” Actually, while in the midst of it, I learned to calm down, get grounded, and actually talk to the cancer. It went something like this: “OK cancer, I’m listening, what is it you want to tell me? I am holding still and listening carefully, so tell me what I need to know. You aren’t going to be here for very long, so tell me now.”

With my journal in my lap and pencil in hand, I would begin writing, and listening, and paying careful attention because I felt my life depended upon it. Actually, it did!

Once I could let go of the embarrassment and self-judgment, I began to live my life more authentically and freely. I accepted myself as human being in a perfectly imperfect body, and that as a biological entity on this earth, things go wrong! I did not engage self-blaming, and I surrendered to not every truly understanding why I got cancer. I read a lot of Carolyn Myss’s writing, and realized I would never wrap my brain around the reasons why. Also, I stopped worrying so much what other people thought and focused more on how grateful I was for every day I got to be ALIVE.

Now, the challenge is to remember these insights almost five years later. I want to hold on to the cosmic kick and the new manifestations of myself that came as a result of living with dis-ease.

I realize I could go on for quite awhile here, so I’ll stop here! Thank you Alice, this is truly an excellent post. I encourage you to take your thinking and knowledge to a wider audience. And if you need a good editor, I know one!!!

Wow, Maureen! Thank you for this incredibly thoughtful and candid comment. I hope everybody who enters my website reads it. Actually, you’re the second person who has suggested this area for my next book. And I’ve got plenty of ideas. But this time I think I need an agent. Got any recommendations?

Alice, I’m glad you’re feeling better! Your essay reminds me of an incident that has always stuck with me – my neighbor on one side had cancer, and my neighbor on the other side told me over the fence that she wasn’t surprised because the neighbor with cancer was so nice and quiet and non confrontational. I was floored that anyone could think that way, and I did manage to say something to the effect that I didn’t believe that was how it worked. I have always thought that this kind of thinking is a confusion of correlation with cause. Even if two things are very strongly correlated, we can never say that one causes the other in any one individual’s situation.

This is an example of the kind of distortion that Ruth Bolletino is talking about. It’s good that you point out the difference between correlation and cause, especially in the case of an individual. This kind of pigeon-holing does nothing to help the cancer patient.

Thank you for sharing Alice- very interesting. As a Health Psychologist I have always been intrigued by mind-body interactions and interrelationships. I love the evidence-based research in the areas you describe– not just because I am in awe of the power of the mind to participate in healing…which I am, but also because I love to see objective biological data confirming things we have suspected or wondered about for decades.